|

My family missed watching the moon landing.

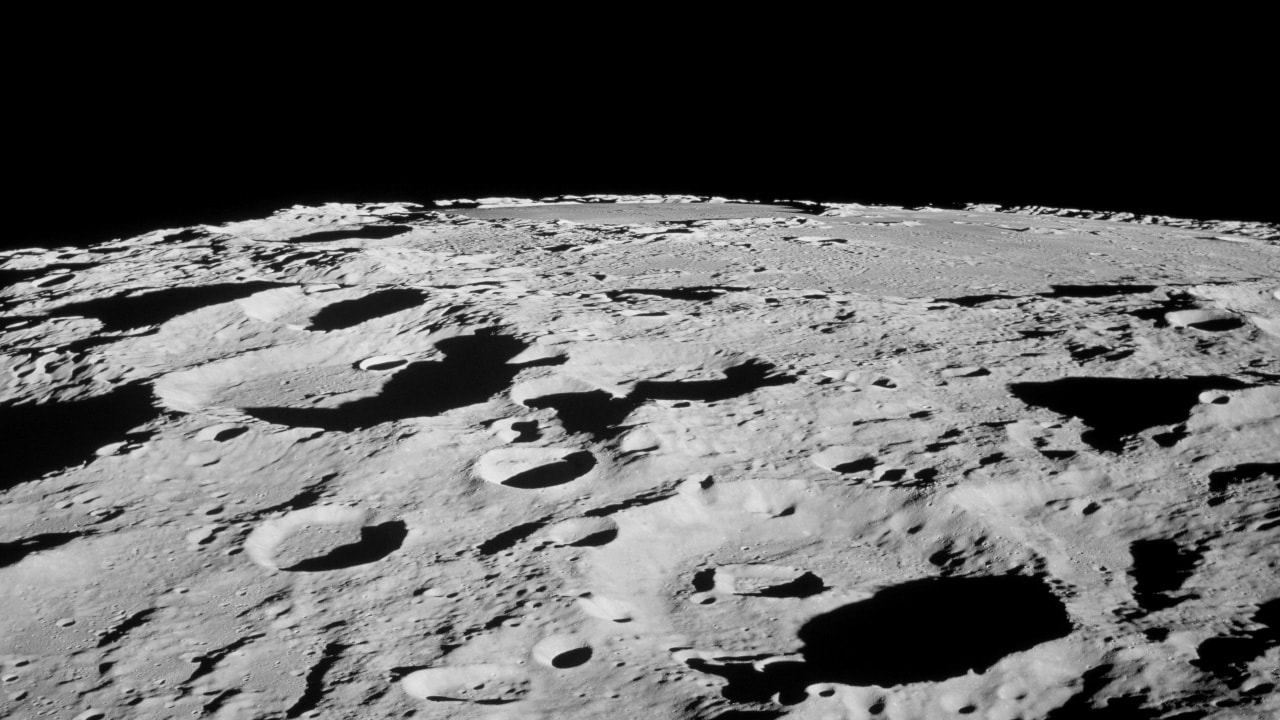

On that July day in 1969, we weren’t home, in front of our television set. Instead, my father had borrowed a cabin in the Santa Cruz mountains from a friend and packed the family off for the weekend. We’d loaded up our board games and Tonka trucks and Herb Albert records, including the album with his big hit “This Guy’s in Love with You,” which one brother jokingly sang as “The sky’s in love with you.” We thought we had everything we needed. We didn’t discover until we arrived that the cabin had no television set. Missing the moon landing shocks me especially because my father worked on the space program. The company he worked at contracted with NASA to build communications equipment. During my childhood, Dad’s lab built antennas that sent pictures from space of weather and planets, even the surface of Mars. My family always told me the Hillesland name was on the moon. I only found out later that, instead of the commemorative plaque I envisioned, my father and uncle, along with the rest of the team, had graffitied their names on a piece of equipment destined for the lunar surface. Growing up, stories about and images of space surrounded me. But we missed those first moon landing pictures. Mind you, my recollections might not be the most reliable, because I was four in 1969. I might be conflating visits to the cabin, or imagining details. But here’s what I remember: we sat in the cabin’s living room, listening to a static-filled radio broadcast and trying to imagine what was happening. We concentrated so hard, as if we could will the pictures from the sound. But we couldn’t. Some writers' experiences give them great stories to tell. Authors might witness pivotal moments in history, or perform amazing feats, or endure great hardships. Those lives might not be comfortable to live, but they can make for great writing. Those of us who have not have those kinds of lives, though, if we write nonfiction, end up telling an alternative version, where we miss the biggest bit of televised history in the 20th century. We have to work with what we’re given. Without the big moments, we have to find the charm, humor, and meaning in what we're given instead. Fortunately, many other readers live without those big moments and can relate to the more ordinary stories. Here’s my story of the moon landing: In my memory, moving tree shadows pattern the cabin floor. I’m fascinated with the wood paneled walls—possibly the first I've seen. The cabin feels much closer to nature, much more of the earth than our house with its mown lawn and waxed linoleum floor. I can feel the weight of our listening to the broadcast, like a thick blanket thrown over the room. I don’t really understand what’s going on. In later years, I’ll watch other space missions, liftoffs moonwalks and splashdowns, but now I only know something important is happening, something I can't picture, because I've never seen it before. No one has. On the radio, Neil Armstrong is taking one giant step for mankind. But I’m distracted. I’m watching the shadows on the floor, while inside my head I’m singing “the sky’s in love with you.” I'm with the wood paneling and trees and blue sky, down on earth while big, unseen events are happening out beyond my understanding.

0 Comments

|

Author

Ann Hillesland writes fiction and essays. Her work has appeared in many literary journals, including Fourth Genre, Bayou, The Laurel Review, and Sou’wester. Categories

All

Archives

February 2024

© Ann Hillesland 2015-2017. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Ann Hillesland with specific direction to the original content.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed