|

After I “finished” The Hat Project, I realized I no longer knew where most of my hats were. I’d added hats during the project and acquired even more since the project “ended.” I’d moved hats around to accommodate the new arrivals. Assuming I had anywhere to go (not a given in COVID times) I wouldn’t be able to find my desired hat without taking down several boxes.

I had to get organized. I created a table listing all the hats in The Hat Project’s Hat Gallery, sortable by color. Then I started opening boxes, inventorying the contents, and tagging each box with a sticky that listed the hats inside. In the middle of this effort, a friend called. When I told her what I was doing, she mentioned how great it was to “KonMarie” one’s surroundings. “I don’t know about that,” I said. “I’m a maximalist.” Some people are taking the shutdown as an opportunity to clean out their houses. Not me. To me, now is when you want your nest extra feathery. Forget cleaning out the closet. Yesterday I bought a fifties vintage coat AND a sixties vintage suit. Plus, I find minimalist interiors depressing. All that white and beige and gray brings me down. Where's the color, where's the fun? I’ve read many articles that advocated turning all your hangers around and only turning them to the right side again when you’ve worn a garment. At the end of the year, you discard anything unworn. I know myself. I’d be searching through those hangers for unworn clothes so that I could wear them before the year was up. I don’t want to get rid of them. Yes, I could definitely tidy up my office (papers seem to explode there) and my bedside table, where old New Yorker magazines go to die. But my clothes? My books? A purge every few years does fine for me. Even the short stories I write have been getting longer. I've switched from 1000-word flash fictions to thirty-page opuses. COVID has forced austerity on all of us, and I’m sick of it. When this is over, I’m going to dress up for everything. I’m going to wear my vintage beaded yellow blouse and my gold lamé coat and a velvet evening hat to the local bistro. I’m going to travel to New Zealand and everywhere else I’ve dreamed of visiting. I’m going to throw a big party with great food and music. I’m going full maximalist on life. Nothing creative ever happens in a tidy way. Every first draft I write (even of this blog) is a mess. I don’t want to live in a white and beige tidy world. I want to live with a lime green sofa and a colorful Mexican tile kitchen table, and a stack of books that don’t fit on the nightstand next to the bed, and ideas for abandoned stories littering my computer, and too many beautiful vases crammed into my cupboards. Yes, I do want my hats to be organized. But right now I’m keeping all eighty of them. And I’ll always find room for another fabulous find.

8 Comments

Every year I write a post about how my writing year went, highlighting how many pieces I had published. But this year is different. I had zero pieces published, for the simple reason that once the pandemic hit, I pretty much stopped submitting work to journals. I made a total of four submissions for the year, when I often make over one hundred. I was already so stressed and depressed, I decided to give myself the gift of a year without rejection. For the first few months of the pandemic, I found it impossible to write at all. Instead, I kept a pandemic diary, thinking that someday I would set a piece of literature in 2020 and would need to remember the odd details. Here’s an excerpt from April: Went to the grocery store for the first time yesterday. Terrible, tense feeling, especially from the employees. Almost everyone wore masks (the one woman I saw without one came in with no cart, obviously to pick up something small. Then she stood too near me.) Aisles set for one-way traffic. I went down the wrong way once, trying to speed through to the other side of the store and avoid a crowded aisle. Of course, then someone turned into the aisle and I had to apologize. Ended up passing a woman dithering over packages of chocolate chips—I think she picked up every kind. Then she had to pass me as I tried to find dried chipotle flakes in the spice rack. I saw two different people wearing special Cleaning Crew smocks and roaming the aisles with wheeled canisters of disinfectant. Met a woman in the toilet paper aisle who complained that last time she came, the store only had some expensive, fancy kind. Now that she tried it, she likes it better, but now they didn’t have it. Aside from the journal and finishing The Hat Project (which I did despite having nowhere to wear hats), I did no writing for months. One day in my journal I put in this cartoon from the New Yorker that said what I was feeling about writing. Referring to my writing, I wrote: “Hopeless, hopeless, hopeless.” So, I wasn’t in a good place for a few months. I started the discipline of going for a daily walk, posting my photos on Instagram. Getting out helped. I also started feeling better once more places opened up. Gradually, I was able to write again, and, in fact, I finished the first draft of the story collection I had started the year before. It was freeing to just write without worrying about publication. “Maybe I should just write for myself and quit trying to get published,” I thought. Of course, there's little point in writing if no one reads your work, so I've started to think about submitting again. Maybe in the new year. So many other important events happened in 2020. The Black Lives Matter protests made me think again about how to be more inclusive in my writing and my reading, and how to better stand up for others and live what I believe. The election season brought additional distractions with its intense dose of hostility and craziness, but also brought tears of joy when Kamala Harris stood up as Vice President Elect. 2020 was historic in so many ways, I'm giving myself a pass on not accomplishing everything I'd hoped a year ago. It certainly would be a good setting for a novel, but it's not a novel I feel like writing now. Maybe never. After a quiet, slightly sad holiday separated from many loved ones, I hope we can get through this latest virus surge. Surly, with a vaccine starting to be available, life will be better in 2021. I hope a year from now I'm writing my usual post about publications and writing successes. Four years ago, on election night, I looked for a nice bottle of wine to open while watching the returns. I reached for a bottle of local wine from a vineyard I knew had a female winemaker. I was about to open it when I noticed the wine’s name: “The Don.” Can’t drink that tonight, I thought, and chose another bottle.

I am not really superstitious. You won’t find me worrying about black cats or tossing spilled salt over my shoulder or refraining from flying on Friday the 13th. However, as a writer, I do believe in symbols. Gatsby’s sumptuous car, Ahab’s white whale, the bridge that Ruth crosses at the end of Housekeeping—all of these symbolically mean more than just a car, a whale, or a bridge. I, of course, employ symbols in my own work: the bicycle in “Aces”, the fire plow in “Two Sticks,” the blue suede jacket in “Angry Money.” So, I couldn’t toast what I hoped would be a Clinton victory with a wine named “The Don.” It wouldn’t be right symbolically. And, OK, maybe I felt I might jinx the election. Because I had been so worried in the election runup. Politically, I’m liberal, but to me, Donald Trump represented the triumph of all that was worst about my country. The sexism, racism, arrogance, and selfish disregard for others he showed were revolting. Beyond policy (did he have any?) his character disgusted me and raised the greatest fears—fears I would not have felt had any other Republican been in contention. Well, we all remember how that night ended. When Florida went for Trump, I felt physically ill, and got sicker as the night went on. I cried, feeling as if someone I loved had died. Perhaps something had: a naïve belief in the judgement of my fellow Americans. That many would choose a person of such bad character to lead our country saddened me greatly. After that, The Don wine seemed cursed. I’d see it on the rack as I dusted, or as I chose a bottle to open, and look away. The bottle had taken on symbolic meaning. I couldn’t drink it until Donald Trump was defeated. This year, on election night, though I hoped to see a landslide Biden victory, I didn't expect it. Also, I knew tabulating results might take a long time. I didn’t sit in front of the TV, but instead read a mystery novel and had a zoom call with the Fabulous JewelTones. When I did peek at the results and saw Florida trending towards Trump again, I panicked. I was only comforted a little when some networks called Arizona for Biden. As the count dragged on, I felt more confident day after day. Yet my anxiety persisted until all networks called the race for Biden today. Tonight, my husband and I opened The Don wine. I thought of waiting for the inauguration, but it seemed more symbolically right to open it today, the day the results were final, declaring that Trump had lost. No landslide victory, which means that we will be battling Trumpism, if not Trump, for a long time. And the sheer number of Americans that rewarded his bluster and incompetence with their votes dismayed me, though it no longer surprised me. It's a victory nonetheless. I cried tonight, not with despair as I did four year ago, but with relief and hope. Good art can change the way you view the world. Everyone who creates art: pictures, movies, comics, books, etc., would like to have their art affect people's world view, to create something that leaves an indelible impression.

I was thinking about that goal today because I saw a Beware of Dog sign. Many years ago, I saw a Gary Larson cartoon of a man standing in a yard behind a tree. A Beware of Doug sign hung on the fence. Ever since I saw that cartoon, when I see Beware of Dog, I think Beware of Doug. (To respect Larson's copyright, I'm not going to put the image here, though it's easy to find online.) Gary Larson is a great artist because he looks at Beware of Dog and thinks of Beware of Doug. His skewed vision has changed the way I view the world. However, he not only had the idea of Beware of Doug, he fleshed it out with an image of an oversized man unconcealed by the tree trunk he's hiding behind, and a traveling salesman about to enter the yard. Doug's face is visible, but only his large eyes, not his mouth, so his expression is hard to read. He almost looks afraid, but maybe he's just watching, waiting to spring. The viewer's imagination writes the story from there. Does the salesman heed the warning? If not, what happens when he enters the yard and Doug attacks? How does Doug attack? What emotion drives Doug to attack? Who posted the sign? Great art also leaves you with questions, ongoing thoughts you have to decide for yourself. Beware of Doug is what I aspire to. But all I can do is write the stories I have and hone my craft so that when I get an idea, I can try to flesh it out in a way that entices the reader to read, and hopefully to think about what happens to the characters after the story ends. I'm not sure any artist knows when they succeed. Sometimes I know I have something, that my writing has spark. Other times I feel like I'm blowing on wet wood, trying to get my story to ignite. Last month I wrote a story too bad to send to my writer's group. I worked on it some more, and still feel it's pretty bad. Meanwhile, I wrote a different story that has a spark of something, even if I'm not sure how well I've executed on it. The new story will go to my writer's group. The old story? Maybe I'll work on it some more, or maybe I'll just let it go. But knowing if a story will change someone's world view? That's way above my pay grade. Literary journals often post in their guidelines that they want beautifully written stories that move them, stories that change the way they see the world. I pay no attention to those lofty criteria, because if I did, I'd never send out anything. Who writes a story and thinks they've just written something beautiful, haunting, world-shaking? I just send stories in and see what happens. Sometimes the journal accepts a story. Who knows why? A story can be rejected fifty times before getting accepted and read with high praise. So much of writing, of life, is just doing the work and seeing what happens. Opening the gate and seeing what Doug does. Every year, I write a year in review post about my writing. It's my annual check-in. How's it going? What did I hope to accomplish? What did I accomplish? As usual, I didn't accomplish as much as I hoped, but I still had some good things happen.

First, I started my Hat Project blog. I really underestimated the time it would take to not only take pictures of the hats as I wore them, but write the little essays that go with them. I also underestimated my desire for new hats! When I started, I thought it would take a year, since I knew I had somewhere in the neighborhood of 50 hats. However, not only have I bought a few more since I started, people have given more to me, with the result that I'm going to be blogging about hats longer than I expected. However, unless I go crazy buying hats or get given a vast collection, I should be finished this year. It's been a very interesting experience. I set out to write an autobiography in hats, and that has meant revisiting happy, funny, and painful episodes in my life. I've also worn many hats out and about, some I'd always meant to wear (my grandmother's hats, for example) and some that I never imagined wearing in public (hello, green feathered hat!). The blog has sapped some of my time and energy away from my fiction, but I have enjoyed the process (except for constantly looking at pictures of myself). And I really enjoy publishing the little essays myself, without having to submit them to journals. Instant gratification and hats! What could be more fun? I did have some fiction published this year, including one story that was nominated for the Pushcart Prize, and one that had a very long road to publication after the first journal that accepted it folded before publishing it:

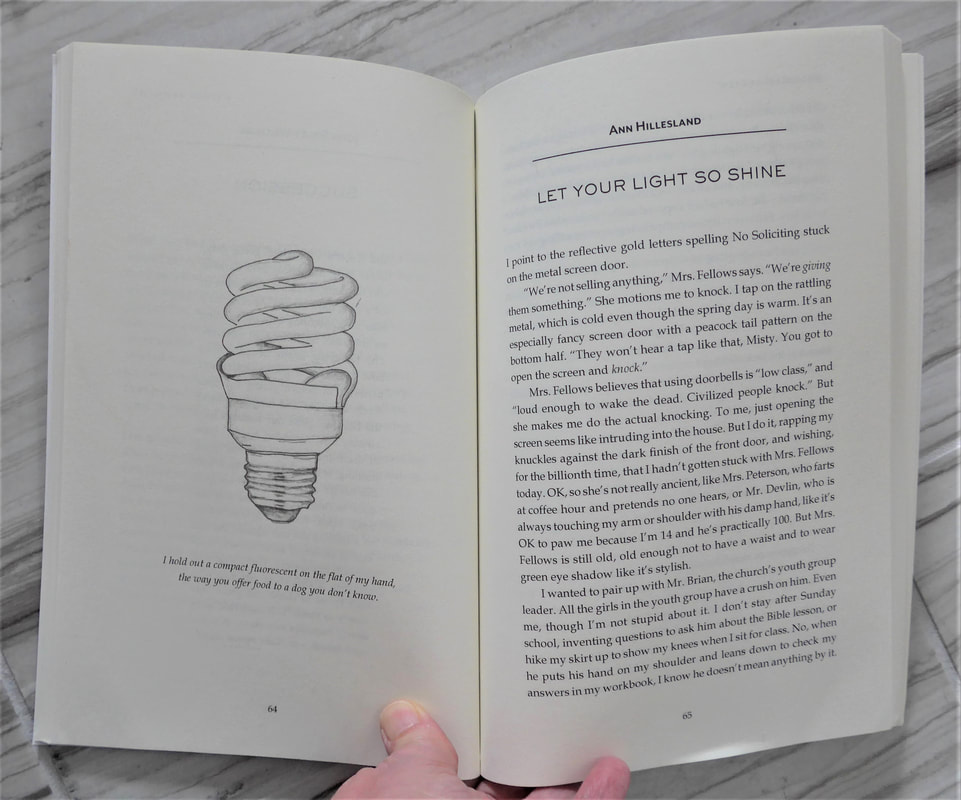

I also had an essay that was very close to my heart published and read on the radio, "Tracking Every Spoonful," in The Dirty Spoon. As the essay was very close to my heart, hearing it read on the radio was a wrenching and wonderful experience, and I feel lucky that my work was chosen. I didn't accomplish everything I set out to do this year. I revised the opening of my novel but have yet to start sending it out again. I made fewer short story and essay submissions than I usually do. However, I did write some stories, including a new project that may end up being a story chapbook or full collection. Time will tell! Thanks for reading my work this year. I really appreciate your support! Thank you to the folks at the Potomac Review for publishing my story "Let Your Light So Shine." I admire the journal and am very excited to appear in it!

This story has a bit of a history. A few years ago, my brother-in-law told a story about how his church was doing kindness ministries, such as handing out light bulbs. I was taken with the idea and decided to write a story about it, with all the characters and details made up, of course. I finished the story and started sending it out. To my delight, after sending it about a dozen places, I got an acceptance, from a well-regarded journal. I excitedly told my husband and a few friends. I followed the journal on Facebook so I could see when the issue came out. And then after a few months, via Facebook, I saw the announcement that the journal was folding. They had just published their last issue. I checked the table of contents, and my story wasn't there. Usually when a journal folds, they make an effort to publish every story they accepted. Not this journal. So I started sending the story out again. One positive from the whole situation was that, knowing one journal had accepted it, I had a lot of confidence in the story. Still, I had to send it forty-five more places before it was accepted. However, I've noticed before that the stories that take the longest road to publication are often the stories that I think are the strongest, and often end up in the journals I like the most. So it is with this story. I think it's one of my best, and I'm very proud and excited to have it in the Potmac Review. I'm absolutely thrilled that The New Southern Fugitives has published my story "Aces" and nominated it for the Pushcart Prize.

A story inspired this story. (Note, there are spoilers ahead, so read the story in the journal before continuing). My husband and I belonged to a group for newcomers to the area, in which we took turns hosting get-togethers. At ours, I asked a couple of icebreaker questions so that we could get to know each other better. One was the classic writing prompt: tell about the best gift you ever got. One man told the story of how he and his brother were given a single bicycle for Christmas one year. When asked whose bicycle it was, their parents told them to work it out for themselves. So they decided to play poker for it. That's the basic setup I took for this story, though of course the details and the outcome (and how the narrator brother won) are all mine. You might remember the pack of playing cards that was a writer gift last year. Every year, my writer's group gives holiday gifts referencing the recipient's work. The Bicycle playing cards referenced this story. The day before Thanksgiving, I was walking through Trader Joe's, my coat over my arm, when I heard something clatter on the floor.

"I think it went under there." The woman behind me pointed to the tall nearby shelves. "Maybe it was a button?" I asked, looking at my coat. While I was looking, the woman, who was probably older than me, bent down and reached under the shelf. "Got it!" she said, getting up. And she held out a black rock to me. "My rock!" It didn't look like much, so I explained. Years ago, wearing my green winter coat, I went to the beach in Mendocino with my husband. As we walked, I spotted this black rock. It's not perfect, but to me it looked like a heart. I put it in my pocket. I have carried it in the pocket of my winter coat ever since. I can reach down anytime, feel the smooth rock in my hand, and be reminded of our love. Sometimes I remember to take the rock out before traveling so I don't lose it in an airplane overhead bin, but sometimes I forget. It's a miracle I've managed to keep it so long. I would have hated to lose it in the Trader Joe's canned goods aisle. "Thank you so much for finding it!" I told the woman, after explaining the rock to her. She could tell how happy and grateful I was. "Happy Thanksgiving!" she answered, obviously pleased. I was reminded again of how important kindness is. She was probably trying to finish up her Thanksgiving shopping. The store was buzzing, carts four deep at every register, large empty shelf spaces where packages of dinner rolls used to be. Yet she had taken to the time to stop and help me. And I was also reminded of how important gratitude is. I was so sincerely grateful for her help that I could tell it made her feel good to have stepped in. Honestly, I wanted to hug her. In writing, I try to practice both kindness and gratitude towards my characters. Kindness, by trying to understand the battles they are fighting. Some of my craziest characters are my favorites, because I know what is making them crazy. Considering their lives, narrators of "Just in Case" and "Dear Squirrel" are doing the best they can. And gratitude that the characters have come to me in fiction. I'm grateful for whatever inspiration sent them my way. So today on Thanksgiving, I'm thankful for kindness, and gratitude, and that I can still reach into my coat pocket and touch love. Many of my friends love Halloween more than any other holiday. What's not to like? Lots of candy, scary (or not-so-scary) movies, and costumes. Who doesn't like costumes, the chance to be a different person, or maybe not a person at all. How about a gorilla? A slice of pizza? A BART train? Yes, to all of it.

Yet this idea that you can only wear a costume on Halloween ignores the fact that we all put on a costume every day: our clothes. Sometimes it's a formal uniform, like the company polo I wore when I worked at a pizza restaurant, or the nostalgic outfit I wore when I worked at the amusement park. Sometimes it's an informal uniform. I spent my early 20s, when I was the youngest person in my department, dressing in tailored jackets and skirts. I decided I would feel less inexperienced if I looked like a professional woman. Every day, we choose a version of ourselves to present to the world, even if the image we want to project is "someone who doesn't care about clothes." I usually don't want to project that image, but if you could see me as I write this, in a mauve t-shirt, red hooded sweatshirt, jeans, teal slippers, and stained ballcap, I would seem like that person. I would also seem color blind. When I go shopping, I turn away from both sober navy dresses and neon orange shirts, because they're "not me." But of course, I'm still me, whatever I wear. By "not me," I mean those outfits don't project my image of myself, or of the self I want to show the world. I started my hat blog because I had so many hats I never wore--I worried they would project an eccentric image. Yet I had bought them thinking they expressed a fantasy version of myself, one that lived the glamorous life seen in mid-century movies, or a modern me that was more confident and stylish. The first hat I ever bought was for a Halloween costume, but most of them I got because I liked to imagine myself wearing them, whether I actually wore them or not. In the end, our Halloween costumes are an expression of our image of ourselves, just as our regular clothes are. In the picture above, part of me wanted to BE Carmen Miranda, wear an outrageous hat and gobs of jewelry. When I wore this costume to a party, someone asked me where I had gotten the "perfect" dress. I had to confess I'd gotten it from my closet--I'd worn it to a company party a few months earlier. You'd think, as a writer, I could inhabit any character I want to, and in a way, that's true. I've written stories in the points of view of women and girls, boys and men. Also a parrot and a hive of bees. But all these characters are from my imagination, from me. Like my Halloween costumes, and my hats, they contain some essential part of me, no matter how far from my daily reality they are. Writing fiction, I get to wear a costume every day, pretend I'm someone I'm not. But somewhere deep inside each character, some tiny part of me is hiding behind the mask. I'm very pleased to have my story "Two Sticks" published in Ellipsis Zine. One day when I was at water aerobics, an older woman told me that her husband had been very involved in the Boy Scouts his whole life. She mentioned that when they had parties, he'd demonstrate how to start a fire without matches. I thought that was a great scene for a story, and went home to work on one, keeping the idea of a man starting a fire as a party trick, but making up everything else about the couple. Of course, in order to write the story, I had to find out how exactly one starts a fire without matches. Fortunately for writers, this kind of research is made much easier by google and YouTube. As I got into the details of fire starting, I learned that the two sticks method, which I'd assumed was the only method, was in fact only one of many ways to start a fire. Looking up the others, I was instantly intrigued by the fire plow. I started watching videos, and after the first couple of minutes of the following video, writing about the fire plow became irresistible. The fire plow is still two sticks, just two very special sticks of disparate sizes, so I felt justified in keeping the title I'd originally written.

By the way, "Two Sticks" wasn't the first story inspired by water aerobics conversations; an different exchange with a different woman in a different class led to the genesis and title of "The Moon in Daytime." |

Author

Ann Hillesland writes fiction and essays. Her work has appeared in many literary journals, including Fourth Genre, Bayou, The Laurel Review, and Sou’wester. Categories

All

Archives

February 2024

© Ann Hillesland 2015-2017. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Ann Hillesland with specific direction to the original content.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed